What if I were to tell you that I had discovered a way to run software projects that’s efficient, effective, reliable, even pleasant?

“Please continue…”, I hope you say.

Up front I’ll let you know this isn’t a new discovery. In fact it’s a story that begins “a long time ago in an office far, far away”. So let’s board a handy time machine as we travel back to the day I started at my first proper Silicon Valley job. A place somewhat like what would be called FAANG today:

Released from HR onboarding presentations, I made my way to the building, floor, and cube where I was excited finally to join the ranks of the people who really knew what they’re doing. Or at least pretty darned close.

But all the cubes were empty. Nobody around. Wondering what to do now, I see someone coming toward me: my new boss, who I would come to appreciate was a brilliant manager. “Are you coming to bug council?” she asked. I had no idea what a bug council was, although it vaguely evoked a picture of serious people sitting in low-slung, high-backed leather swivel chairs. Perhaps deciding the fate of the universe.

It turned out to consist of everyone on the product team sitting in a meeting room, each holding a printed copy of the product bug list, sorted by priority. P0 at the top (CS numbering, and also supposedly because a director had wanted something more even urgent than the original P1, like the guitar knobs that “go to 11”).

Working down the list our lead called on whoever owned each bug to give a status update, highlight any factors blocking progress, and answer any questions from the team. Everyone was on the same page. Literally. Sometimes the bug needed to be updated–change its priority, add another bug that was blocking it, re-assign it to another team or mark it as to be fixed in a future release. Although this was before Wi-Fi, someone had a laptop plugged into a wall socket, making the requested bug updates in real time. Once the P0-P2 bugs had been covered, the meeting was over and everyone went back to their work: fixing the remaining bugs.

It seemed so simple: ship good software by listing all the bugs in priority order and work down the list fixing them until none remain. But I would learn that beneath the simplicity there were deep psychological forces driving the process, exerted through a set of four key principles designed into the bug tracking system we used.

That system lives today, long ago re-written as Bugzilla. Back then it was called BugSplat. Developed in house in a grass roots effort and one of the first pure web apps, its functionality had been honed to meet the needs of its users, by its users. Premium dogfood.

The first key principle was that every task that needed to be done went in the system. New features, missing documentation, confusing UX, bad performance, and of course actual bugs reported by users. We treated everything as a bug. BugSplat was the only project planning system. It meant that all plans in the organization, managing towards whatever goal, could be conceived of and viewed as a projection across this single coherent set of bugs. More on that later.

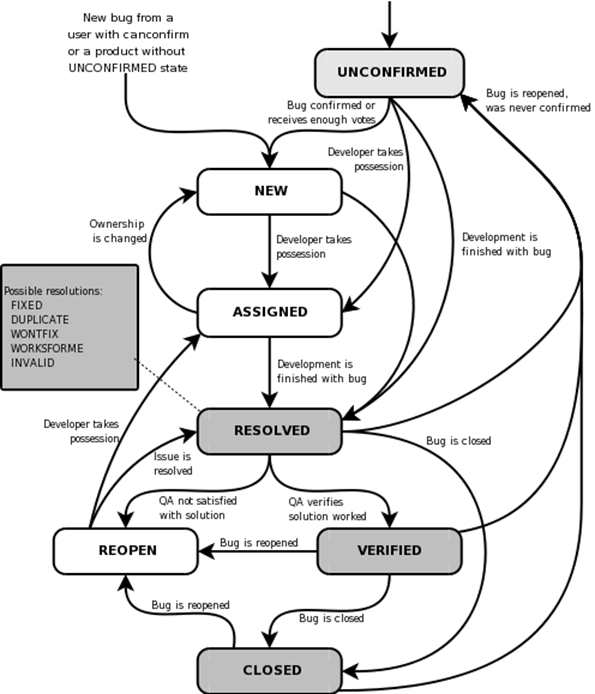

The second was that the schema for a bug record was universal, for the most part fixed, and opinionated. Opinions informed by long experience using the system. The diagram below gives a flavor. Bugs aren’t just open or closed. There’s nuance to the state of a bug. If that isn’t captured in its schema in a consistent way, it’ll end up captured as confusing text notes, or just lost. By using a single comprehensive schema that captures bug state, priority, severity and interdependence, the system prompts its users to also be consistent clear and specific in their process.

The third principle was that only one person could be assigned responsibility for a bug. One person at a time that is — bugs could be and often were re-assigned as needed. It’s only with unambiguous responsibility captured on a fine grain basis that the bug system can be used as a project management tool. That way it’s easy for anyone (including their manager) to see what an individual is working on, what they’ll be working on next, and what they done recently. It’s easy to see if someone has become overloaded. Everyone can enjoy warm fuzzy feelings of ownership and achievement.

The last principle is that the way lists of bugs were viewed was as the results of powerful queries. In contrast to the consistent fixed record schema, queries could be rich, expressive, savable and sharable. This allowed users to curate and share a set of bug list views that suited their particular purposes and context. That’s how the bug council list was created: as a query for all new and open bugs against our product and the current release under development, sorted by priority and then shared with the team. An individual developer would probably want to focus on a list that showed all bugs assigned to them, across all products and releases, again sorted by priority. A security engineer might be more interested to look at bugs sorted by severity rather than priority. The thing to note here is that it’s the set of queries that’s endless: the bugs themselves don’t need to change schema to accommodate these diverse purposes and contexts. Everyone can make their own punch list. Clearing those punch lists is how progress is made.

With the benefit of a couple decades reflection it was these four principles, baked into the bug system, that formed the rails upon which our product release trains ran.

Since all this happened a long time ago and apparently worked pretty well, if we got back in the DeLorian I suppose we should expect to find that people today are doing something as good or better.

My experience however has been: that’s not exactly what happened. The first thing we’d notice (besides Dr. Evil defrosted) is that bugs are now called “issues”. Presumably this came from a desire to give the commercial bug tracking systems that followed Bugzilla (JIRA and its ilk) a broader appeal. But that’s at odds with the etymology: the word bug pre-dates computers.

We’d also notice that the web apps with which software projects are managed have a primary focus around source code control (that’s a confusing way to say: everyone uses GitHub now). GitHub creates a dilemma on how to manage bugs: use a bug system tightly integrated with source control (they call that: GitHub Issues), or not (e.g. JIRA for bugs but GitHub for source code)? It’s a tough decision and opinions definitely differ, but I’m firmly in the former camp. I like my bugs tightly snuggled up with my source code.

Why though? The first reason has to do with user management: if we put bugs in JIRA, now someone has to ensure that users who need to see bugs are provisioned in JIRA. That’s at minimum a hassle and might also incur extra cost. But if bugs are in GitHub Issues I know that whoever can see the code can see bugs, even if they’re in a different organization. For open source projects that’s a big benefit that avoids balkanizing project membership. The second reason is that tight integration allows some pretty useful functionality. For example automatic listing the set of bugs fixed in release notes and easy referencing back and forth between bugs and pull requests. It’s also nice to have consistent UI between code management and bug management. Lastly unless GitHub Issues are (is?) disabled, users are going to file some bugs there no matter where you think you’re managing your bugs. And now you have two problems…

So assuming we’re going to try to use use GitHub and its Issues as a unified bug and project management system, how does it measure up against our four key principles of yore? (Spoiler: not too well).

First principle: do all project tasks get treated as bugs and entered into the bug system? Well that depends on who’s running the project bug in my experience generally no because (see below) GitHub Issues is so feature-poor that people end up one or more other project planning systems alongside it.

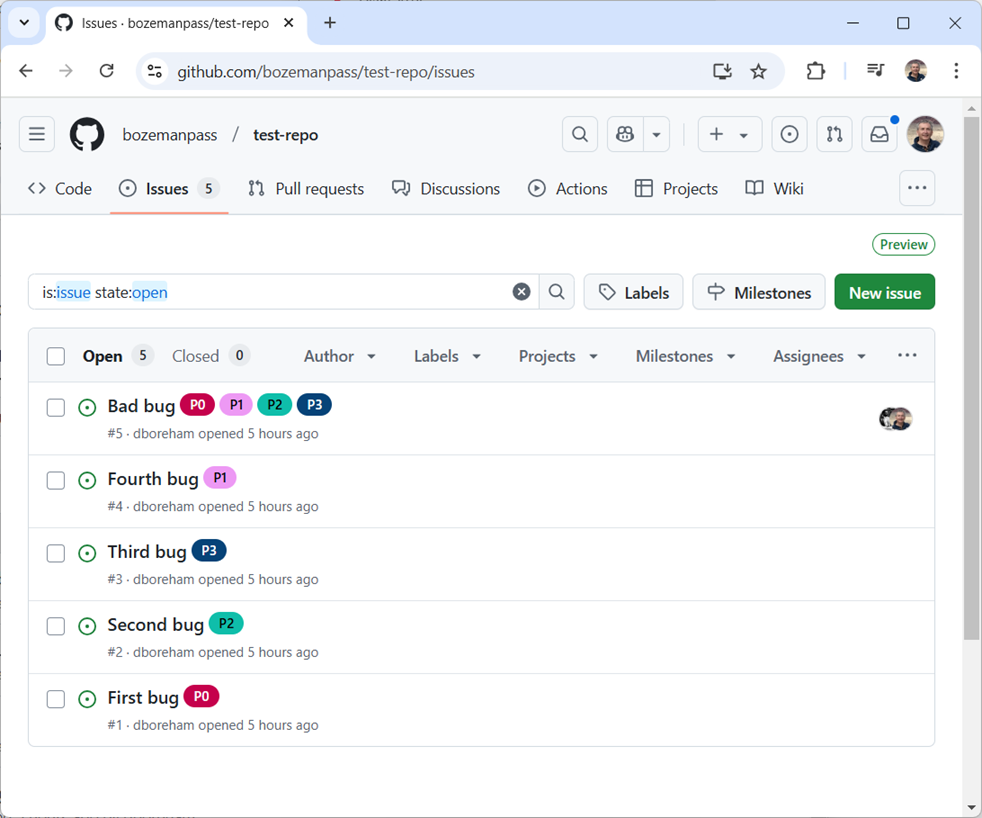

Second principle: bugs (sorry…issues), should have consistent opinionated schema that supports the development process. GitHub Issues scores about as badly as one could imagine here. Out the box there’s very little schema. All you get to add to that are user-definable labels. Labels are defined per-repo (and recently also at the organization level) but everyone gets to, and usually does, define a different set of labels. Regardless how creative you get with labels, their limitations are going to be an…issue. For example I can try to define labels for bug priority: P0, P1, P2 and P3. But since any label can be assigned to a bug, there’s nothing to prevent a bug having all priorities at the same time (see “Bad bug” in the screen shot below).

Third: bugs should be assigned to only one person. GitHub Issues will let you assign one bug to as many people as you fancy. I’ve seen examples in the wild with 10 assignees. Bad bug below is assigned to both myself and Thomas. Diffuse responsibility has entered the room.

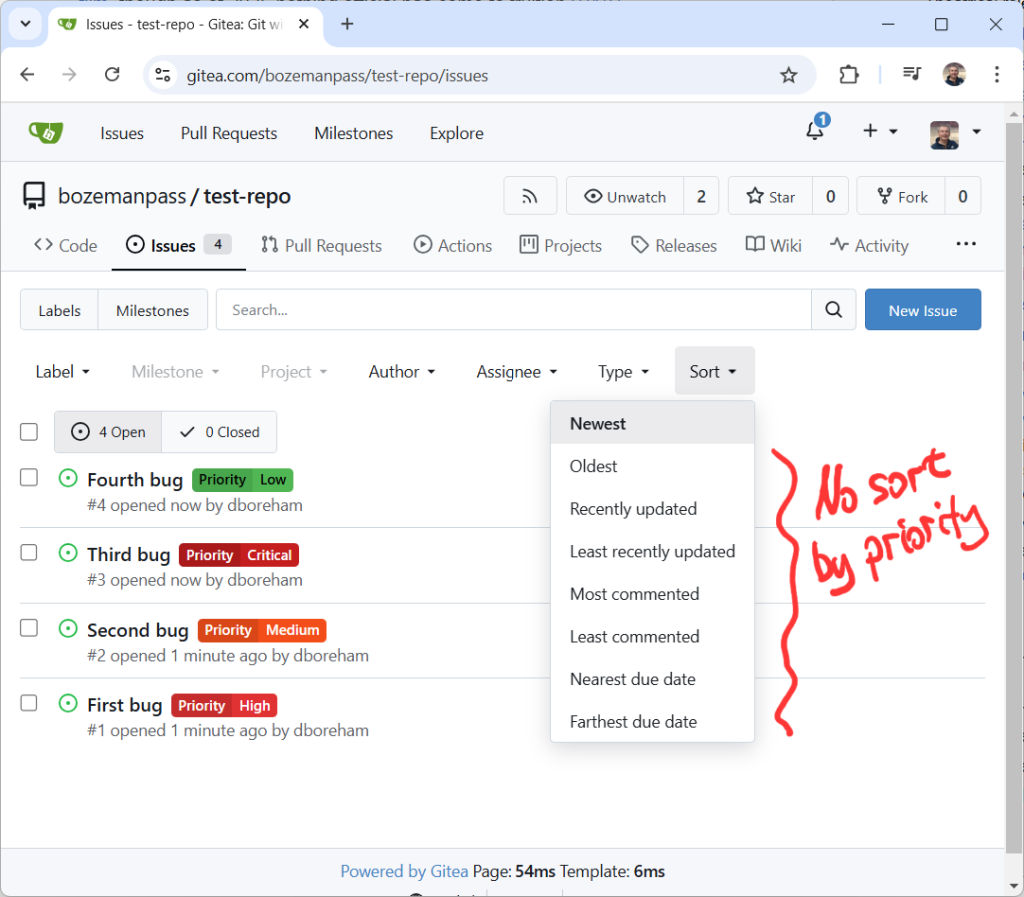

Fourth: flexible queries. Even before looking at GitHub Issues’ query capability, its lack of quality schema makes any querying you can do less than very useful. But that notwithstanding, queries are limited to equality match on label, owner and assignee, with sorting only supported on create and updated timestamps. There’s no way, for example, to query for the bugs resolved by a specific person, sorted by resolved time. And of course there’s no way to make the bug council query: bug list sorted by priority, because there’s no priority field and no way to sort on it. There’s also no way to save or share queries but you might try to copy a query URL from the address bar and save it somewhere for later pasting.

Because GitHub Issues at present does fair pretty badly on our four principles, any attempt to manage projects using it alone is going to be quite frustrating. Is there an alternative to eternal frustration? We might try to persuade Microsoft to add the missing features, but the word in the street is this won’t happen because there is a Microsoft JIRA-like product that almost nobody has heard of and Microsoft would prefer to try to sell you that rather than improve GitHub Issues. Just sayin.

There are of course some GitHub alternatives such as GitLabs and Bitbucket. Generally those offer superior issue management functionality to GitHub but still don’t measure up on our four principles.

So we’re In a situation where no existing commercial service has the features we want. In that case the best available option could be to pick a good open source project in the same category and then add those features to it. This doesn’t even need in-house expertise or direct sponsorship arrangements with the project team because there are independent developers such as the team here at Bozeman Pass who will (for a modest fee…) undertake to add a feature to any open source project. This service includes gathering the client’s requirements, coding, testing, creating a pull request and ultimately engaging positively with the project team to have the new code “upstreamed”.

Let’s take a quick look at one such feature that we added to a project called Gitea. Before we began work on the new feature, Gitea already has some upgrades compared to GitHub including support for “scoped” label sets which are a way to denote that a label should have only one of a number of possible values. This capability can be used to implement fields with priority semantics such as in the screenshot below where we have defined a priority label set with possibly values: low, medium, high and critical. Note that as-is although Gitea can represent a priority field, it can’t sort the bug list by priority.

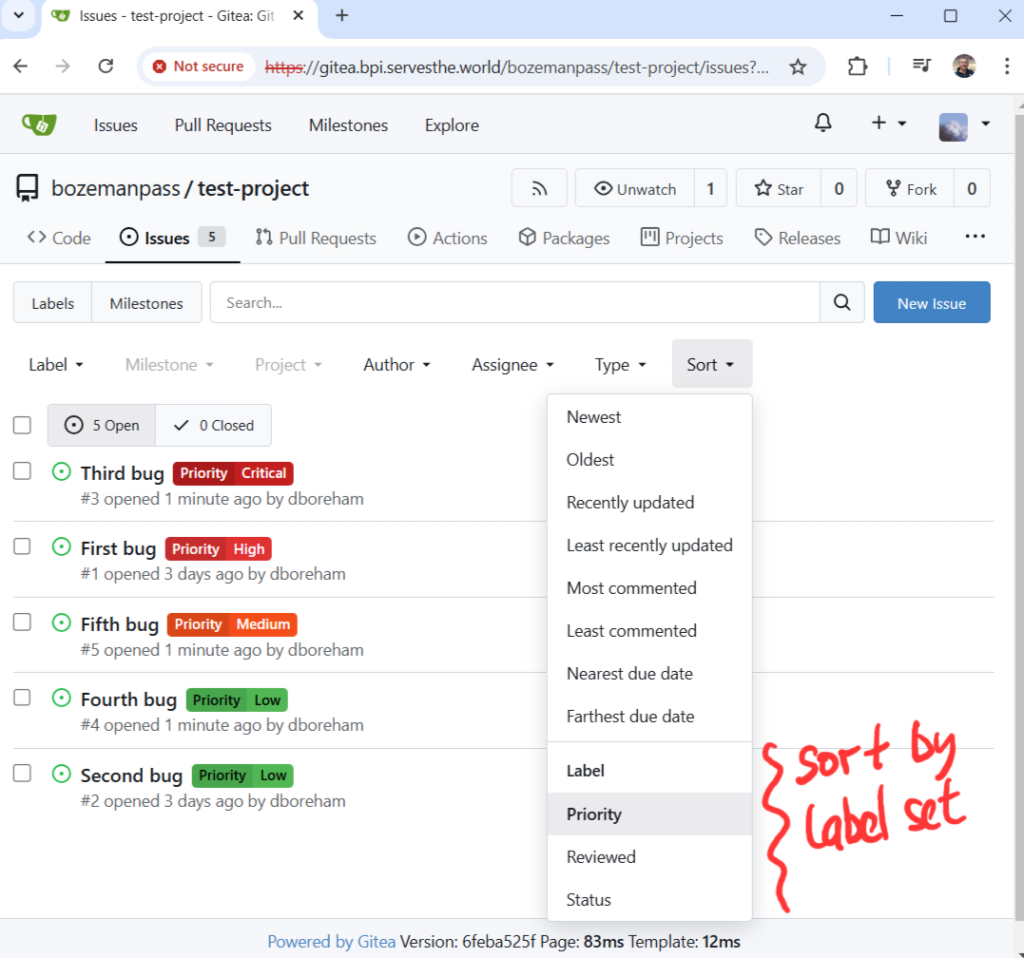

Enter one of the features we’ve added to Gitea. It aims to add that missing sort capability. Although it doesn’t take huge code changes to add the feature, as you can see from the comments on the pull request there is often a few unforeseen concerns and associated accommodations needed to complete the upstreaming process. Here’s the result, finally a priority sorted bug list is possible with a GitHub-like system:

Beyond this current work, we have the goal ultimately to add the remaining missing “four principles” features to Gitea.

Then we can get back to creating software the “bug council way”.

Watch this space!

Recent Comments